My, but the response on covering plus-sizes was intense when I asked for article ideas on the Facebook page! Thank you for the input!

Appears many of you who are “busty lasses,” larger than size 18, and plus-size need to know more about historical patterns suitable for your “stout” figure and how to trim garments with appropriate proportions.

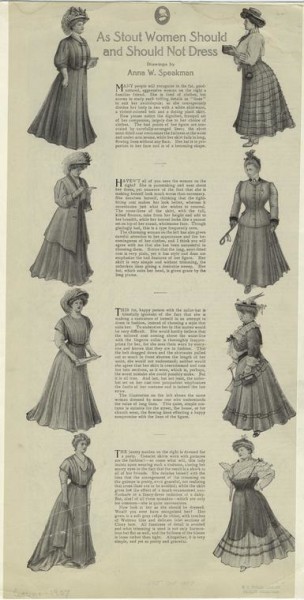

You were also curious to find out if our full-figured 19th century ancestors wore the same styles as the mainstream fashion or simply wore wrappers all the time. (Hint: they wore the latest modes with aplomb.)

To help, I’ve put together a list of items and tips you can incorporate into your period sewing and think about when dressing your lovely larger figure.

A note: “curvy” doesn’t always mean “plus-size.” Even though this article is directed to larger sizes (due to the requests), if you have curves, these tips will be handy for you too.

[Small disclaimer: I personally am not plus-size in a modern wardrobe, being a good size US 14. However, I have large hips, small waist and DDD bra cup. So I understand a bit about full figures. I would love to see other sizes give their insight in the comment section here.]

First thing: Wear a good fitting corset – everything else is built on this so it’s SUPER important. Honestly. Doesn’t matter if it’s slim Regency, full hoop skirt fashion, or 1890s leg o’ mutton sleeves to hide the arms. The CORSET IS KEY to a proper historical silhouette.

In regards to corsets, straight seamed panels seem to be better suited for larger curvy figures, especially if you want some minimization. You’re probably thinking, “but gussets help smooth corset panels over curves.” Yes, gussets DO allow for a svelte look. They do help to cut the corset further into the waist area while providing bust & hip support. I won’t argue that.

It’s simply that the straight seamed panels have the gusset shape built in. Gussets are perfect for smaller busts and hips and for those larger women who want to emphasize their assets. 🙂

As for patterns, the Truly Victorian #110 pattern is fantastic, but you must pay close attention to selecting your size to cut. Laughing Moon #100 is good but doesn’t give quite the tighter waist shaping that curvy girls need (not enough of the gusset shaping added to the straight seams). However, if you carry weight in the belly/abdomen area it’s a good pattern to start with. For more on fitting larger busts in corsets I highly recommend this fabulous article on Foundations Revealed.

Stay modest in the cut of your costume– no very low necklines. It’s okay to be revealing, but not a wench. Curvy girls look best when the gown is fitted well to the figure, emphasizing the curves, but not over-exposing them. This goes for dinner bodices with V or low rounded necklines as well as for ball gowns.

Although, in staying modest, give space to the neckline. Cut down a rounded jewel neckline just a tad to give the neck flesh more room and not make the head look cut off. Shallow Vs and rounds allow for the full bust to “breathe” and not look so confined.

This isn’t to say you can’t or shouldn’t make a high, round neckline bodice. Oh no. This style was seen in many decades – the 1840s, 1850s, 1860s & 1880s primarily, even into the 1890s but with extra collars & trim. Merely give a little bit of ease around the neck seam. And goodness, utilize those waist darts to smooth the fabric over the bust to waist.

Speaking of darts – don’t sew them up in your mockup before fitting. Pin up the excess fabric at the fitting to make two or three darts that allow the fabric to be smoothed around the torso. Follow more fitting tips in this video tutorial.

If your bodice or corset is too small/tight, think about adding an extra panel between the side and side back pieces. Besides the extra width, you get more seam allowance to play with for fitting and tightening the fabric to the torso.

Reduce the size of your sleeves. Your arms may already be large; why add to their girth with super wide sleeves?? It may sound contradictory – needing smaller sleeves for larger arms – but it’s a trick to slenderize the look.

For form fitting sleeves from the 1840s, and 1860s to 1880s, keep the ease minimal on the upper arm, like only an inch or so in circumference. Of course, movement will depend on a well-fitting armhole as it relates to the bodice it’s sewn into. If your sleeve has too much fabric and your arm swims in it, try these tips to taking it in.

For wide sleeves such as puffs from the Regency Era, 1830s, 1890s, and evening gowns of the mid-to-late decades, cut down your puff sleeve pattern to where you get the effect of a puff but not the width of fabric. Too much fabric around a full arm will add visual weight or make it appear larger than it is.

Reduce the width of the puff by making vertical cuts and folding the pattern up evenly. Make sure not to reduce the cap seam line too much. You need at least 1.5″ larger in the sleeve to show any gathers for a puff.

Also, lengthen the puff sleeve. A number of available patterns offer a puffed sleeve that’s very short. I know modern cap sleeves are *the thing* but not so in historical styles. Add length to the hem straight around or simply bow out the hemline to where the pattern is lengthened in the center but stays the same underarm seam length.

Don’t weigh down trim if you’re not comfortable with it. If you’re concerned, be conservative with trim – one large hem ruffle; basic sleeve cuffs; ribbons tacked on flat and not pleated or gathered.

But I want you not to hesitate to add trim either. The key here is to make the trim larger in proportion to you. Don’t add a 1/4″ or even 3/8″ ribbon around the neckline if you are a size 22. It will look like an afterthought and not flow with the entire design. No, use a 1″ or wider size.

If your skirt has to cover 52″ hips, that hem will be wide too. Don’t go slapping on tiny rose buds for decoration.

Think *bigger* and don’t worry about too much. You’ll most likely know when it’s too large as it’ll start looking like a masquerade, fancy dress, or Halloween costume to you. Trust your instinct here!

Remember, though, to increase the overall size of your trims about 10-20%. Pleats should be wider – even an extra 1/4″ can make a difference. Visible pockets should be cut larger. Sleeve cuffs and collars need to be enlarged from the pattern.

Accessories too: hats should frame the face, so that bonnet brim may have to be cut longer and deeper for a rounded face. Reticules should also be cut bigger to compliment wider hips.

And yes – larger women wore the same styles and same trim designs as other smaller women. Skirt panels were still cut the same, just wider and perhaps longer. Sleeve shapes remained the same. I encourage you to constantly study and view original photographs, paintings and antique garments to notice the details.

Re-think horizontal. Nowadays, horizontal stripes are a no-no for plus-sizes. True, they do make the dress appear wider than desired. But in the 19th century you WANT to have a wider hemline or wider sleeves/shoulders so as to emphasize a narrow waist. Use this to your advantage!

Just because you have hips or are a busty gal, don’t knock extra padding for the historical silhouette you’re going after.

For example, I have wide hips at 46″ BUT… my back side is rather flat. The Truly Victorian Imperial Bustle (lobster tail) gives me the full back protrusion I need for the Bustle Era. To get the late 1880s shelf I need to ADD a pad on top of the Imperial bustle. Ack! That’s a big back side. Well… at least it seems to me.

(Listen to podcast episode #7 on working with your specific body type to achieve that historical silhouette.)

Indeed, it’s how the final look is viewed by others (not yourself in the mirror as that’s plain subjective). The confidence you exude while wearing your ensemble goes a long way too with the look you’re going for despite additional padding. 😉

Pay attention to the clothes in your modern wardrobe. Transfer the same guidelines to the historical costumes as you did when picking out the t-shirts and dresses: v-necks, dark colors on bottom, 3/4 length sleeves, particular colors people say look good on you, armhole shirt seams that sit on the shoulder and not hang off so everything looks baggy, etc.

Be willing to accept your measurements as is. No cheating on them! Our 19th century ancestors made the clothes to fit the body they covered. No off-the-rack items were really available (except perhaps undergarments).

It’s only contemporary sources that have told us we all have to fit into a size 8 or size 16. To heck with that when making period garments! Fit YOUR body, not the girl on the cover of Style…. or even in the period fashion plate that’s, again, an “ideal” of the age.

Work on your fittings:

- Open out those shoulder seams to allow the fabric to cover the fleshy shoulder instead of pinching tightly

- Keep the armholes high under the arm, then cut them larger around the top half only to help prevent cutting into the flesh

- Use up to 3 waist darts in front to bring in excess fabric at the waist

- Add extra width in skirts evenly to each panel instead of only centers and sides

- Cut waistbands to your corseted waist measurement over undergarments and with a little ease; fit skirts to the band length with darts and seam allowances

Recommended pattern lines:

- Truly Victorian

- Laughing Moon

- Past Patterns

- Simplicity (watch for fitting issues)

- Period Impressions

My final thought for the stout ladies is a question: Are you bringing your 21st Century mindset to your historical costuming?

Truly. That view of what you *think* you look like in costume is based a whole lot on your 21st C. mind. Heavy-set people have existed throughout all generations of people. Don’t let the prevailing world view of plus-size get you into a tizzy over how you should wear a Victorian dress.

Wear bright colors if you want. Dress as a puffy cupcake if it makes you happy. But most of all, keep at it!

If you fall into the “stout” sizing for Victorian ladies, what’s been the best technique you’ve used for flattering costumes? Share below so we can all learn.

Great article. A note: the photo of the 1900 lady in a corset is obviously touched up. They did that a lot to reduce the waist size. Take a closer look at the waist and you’ll see what I mean. Most of the photos with ladies having an extremely small waist in relation to hips are touched up.

One of the things I truly hate about mockups is the waste of fabric, sometimes it can be used as an interlining if the fit isn’t too bad, but sometimes it just goes into the ‘cabbage’ pile. I did find an occasional source. Yard sales. Sometimes you can pick up a quilters stash for dirt cheap and since as a mockup the side itself doesnt matter, I use the wrong side as the right side so my markings will show better. Darker fabrics of course are less usable for mockups, but work just fine for interlinings or hem facings.

Great tip!

And totally true that mockups can take SO MUCH fabric.

Well, 4 years after you posted this, and I already follow you on facebook, but… I am poking through the internet trying to find images of fuller bodied women in stays, particularly around 1780s. I’m starting to feel like curvier & fuller bodies lean towards 19th C and later clothing. Search “plus size stays” was spectacularly unhelpful. Any thoughts on better search terms or other bloggers/reenactors to look up that might be closer to that style?

Oh.. I’m not sure there. I do know of a couple Facebook groups that concentrate on research and sewing of 18th C stays. You might check there.

Do you have any tips for a survey girl learning how to draft historical patterns for the first time? I mean Most of the patterns I love are in specific sizes so I have to learn how to draft and alter patterns. I am basically teaching myself how to do all of this on my own. Its frustrating.

If you have no pattern drafting experience I’d recommend starting how to draft blocks. From blocks you can design all other styles including historical cuts. For a modern resource (and where I learned flat patterning from), I recommend Helen Armstrong’s book: Patternmaking for Fashion Design (Amazon aflink). There’s also some more historical methods for drafting, like in Frances Grimble’s books. For fitting and tweaking patterns, the book The Complete Photo Guide to Perfect Fitting by Sarah Veblen is worth getting.

I’m a size 26 au and I struggle to fit garments as I have very large hips plus I struggle to pattern make period costumes and stays your article is totally awesome but I’m totally struggling

It can be SO challenging to fit our large, curvy areas! Don’t give up. Keep making those mockups. and you’ll learn more about your own figure as you go along and your work will keep getting better. You can do it! 🙂

I just found your article. I have been struggling with how to proceed to create a Victorian look being just slight larger than the “standard” woman. You gave many great tips and places to research further, thank you. I love your tip on the sleeves and all of the pictures you posted for inspiration.

You’re welcome, Jean. Best of luck as you move forward!

Love this article — thank you so much!! I really, really appreciate all the pictures of larger ladies that you included in the post, too, as we seldom come across these.

You’re welcome! I have these photos on my Pinterest board(s) and also have several friends with specific “large size” people photographs on their own boards. The photos are out there for research, and I’m so glad they are! Proves people of all sizes existed in the past. 🙂

Yes!! It’s all in a proper fit with feeling beautiful and authentic in period garments. I made 2 Victorian ball gowns with “Truly Victorian” bodices (1860’s and 1890’s). I just wore them over an inexpensive ($15) corset from eBay, wearing it higher for the 1860’s silhouette. I really recommend Truly Victorian, her measuring and fitting instructions really give a custom fit!! Thanks so much for this article!!

I re-strung my corset, with 3 sets of strings instead of 2, so I can lace my waist tighter without constricting my ribs or hips. It works well for my fluffy figure.

Thank you from France! Sorry for my terrible English. Your posts are incredibly interesting and refreshing (brains and soul are happy), your tips are always useful. I am very glad to hear you are interested in 18th century dressmaking too. Thanks to you I pre-ordered the American duchess’ book.

If I may, I would ask a question about a Emile Pingat ball dress ca 1864, Met museum Accession Number:C.I.69.33.12a–c. Is the bottom of the sash stitched to the skirt or does it hang freely? and if it hangs, what would you underline it with to make it hang evenly? (because mine is underlined with heavily starched tarlatan and anyway it swings and refuses to lay flat nicely on my skirt worn over a big elliptical crinoline + quilted petticoat + thin petticoat (I want you know I like +++petticoats too).

Best regards

So happy to have you part of our Joyful Community, Christine!

My guess is that they are tacked to the skirt to hang that way. To keep in place without tacking try stiff organdy or light buckram and pin/sew to the waistband while wearing the skirt (have a friend help) or while it is on a dressform so the placement is correct. Tacking, however, can be temporary or easily removed if necessary. Hope this helps! 🙂

Thank You., of course it helps. I Will try Both buckram And Tacking, because i want my trimming, antique black lace, to look good. Take care.

Christine,

I have one question: Are you a yoga teacher? Your English is perfect!

I just found your article. It is very helpful and quite well written. However, I have one question. Why is it that “Busty” is always assumed to go hand in hand with large or plus size? I have really wide shoulders, a plus size middle but hardly any bust. It is extremely hard to figure out pattern size or even to buy clothing, especially period clothing. We participate in cowboy action shooting, sanctioned through SASS (Single Action Shooting Society). The period we dress in is Late 1800’s to barely in the early 1900’s. Think Gunsmoke, Lonesome Dove and that is what I wear to shoot in. Wearing leather holsters for my revolvers. I am about a Women’s 22, but it is very hard to find costumes to wear. They are very pricey to purchase, if I can even find my size. There fore I really am looking forward to making some period correct outfits to save some money. Thank you for the article, I think it will be rather helpful for me.

Glad you’ve found it helpful for moving forward in your sewing!

I think it’s general that larger sizes have larger bust cups – but that is not inclusive. I know many women that are in larger sizes but sit in a B or C cup size. You do have to take into account the larger bust circumference, yet that doesn’t always translate to a larger bust cup. Take a look at your back width. That’s where you might need to add instead of both front and back there at the shoulders and horizontal bust line.

I’s been several years since you posted your article, and I’m so glad I found it. I don’t feel as self conscious about wearing my new costume. As a size 22 woman with a small, almost negligible hourglass waist, I never thought I would be able to pull off a corseted Victorian look. (Technically the waist is smaller than the bust and hips, but only by an inch or two, so I look more pear like), Your tips about making the dresses fit to MY body were spot on.

I’m from Canada and we are in the midst of celebrating our 150th anniversary! I’ve been asked to participate in a “Steampunk Strawberry Social” doing Balloon Twisting to help celebrate. I need to dress the part, hence my interest in actually making a period gown.

July 1st however, is the day I want to be out and about in my period costume. Canada Day will be awesome in 2017! Add to that, the village I live in will be celebrating its 200th anniversary next year. So I will have lots of opportunities to my period costumes.

I can hardly wait to receive my first corset (in transit to me now) and see what it can do to help with my shape. The point you made about the extra support is very interesting. I’m hoping will feel a bit of relief in my back also. I’m a novice sewer, so I’m having a professional help me with the gowns. But ultimately, I’m less worried about my 21st century view of myself now. Thank you very much!

SOO happy you found the tips helpful! And what exciting events you have ahead of you for dressing up fun. 🙂

Cheers and thanks for reading!

Jennifer

I’m tiny, but busty. A 26″ princess waist is perfect for princess seam eras, but as soon as I tried high waist regency, I was so embarrassed with how my dress fit! I’m happy I found this. I might be able to tweak my design enough to balance the look. Thank you so much!

*Raises hand* I am guilty of 21st mindset while sewing period clothes. It is a hard habit to break

Your comment on sleeve size were right on. I made the Mantua Maker 1825-1830 dress in a size 30. I used the size 6 upper sleeve and size 12 lower sleeve and it fit perfectly and was in proportion, and quite large enough!

Thank you for sharing. I rarely see paintings of “oversized” ladies. Noone shares them. I love to wear my corset. Feel more slim although my measuring tape tells me something else.

Very interesting and informative article. To me, corsets looks uncomfortable but I’ve never worn one so I imagine they could be made to be comfortable. It would be fun wearing a dress that fits my body. Thanks for the information.

A corset which is properly fitted and not laced so tightly that you can’t breathe can actually be quite comfortable. It will never feel like wearing a t shirt and yoga pants, but as a bustier lady I find that the extra support is a lovely thing

Great advice, and wonderful images for illustrating your point! I’m currently [mentally] working on another project, semi-historical, semi steampunk, semi something or other, and just blogged about thinking through style lines for the bodice which will not be unflattering on my topheavy, thick waisted figure. I had a good rummage through some ‘large Victorian lady’ images as well.

What a great article! So useful and informative. Thank you so much.