This tutorial is dedicated to Corinne Pleger who taught me the beauty of cartridge pleating in July 2000.

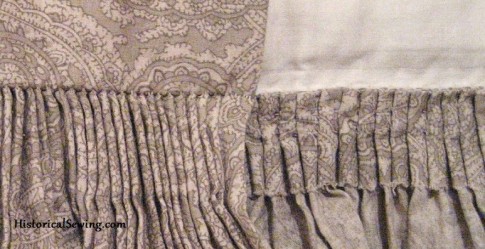

Cartridge pleats are eye-catching! Neat little pleats stacked in a row, stitched together and standing at attention. Those little pleats do a heck of job too with getting an enormous amount of skirt fabric into a tiny waistband!

If you’re ready to tackle this common method of pleating in the mid-19th Century, let’s get to work on how these pleats are actually made. Although cartridge pleats are found on sleeve caps in the 1830s, we’ll stick to gauging skirts in this tutorial.

Cartridge pleats (also known as gauging) are used when a large width of fabric needs to be fitted into a small space. As opposed to the other types of pleats, cartridge pleats are seen throughout historical fashion but practically disappear in the late 19th Century. Because they are completed by hand, they didn’t work in the new, mass-produced, assembly line garments.

Cartridge pleats are characteristic of historical sewing. Found on straight panel skirts of the late 1830s through 1860s and on full sleeve caps from the 1830s to 1860s, these pleats are very easy to create and can be adapted to all sorts of fabrics.

Supplies:

The skirt to apply cartridge pleats and finished waistband

Buttonhole or strong glazed thread that matches fabric

Long hand needles such as embroidery

Marking pencil/pen or Tiger Tape

Safety pins or long ball head pins

Overview:

Cartridge pleats are made from 2 or more rows of uniform hand basting stitches run along the top edge of the skirt. The rows have to be exactly matched for perfect pleats. The stitch threads are pulled up to form the pleats that are then whipstitched to the waistband.

Cartridge pleating stitches are placed in evenly-spaced rows. The stitch marks vary and will change with different fabrics and for assorted projects. Make a sample using different markings on your specific fabric to find the best placement.

The spaces between the stitches can also vary for how full you want the pleats and the bulkiness of your fabric. Wool will have wider spaced stitches than cottons and silks.

Step 1: Determine Area for Cartridge Pleating and Prep

Piece your skirt panels, finish the hem, then mark the allowed skirt length from the hem up to the top at center front, center back and sides. Allow an additional 5 inches for the pleated top.

Finish the raw top edge of your skirt before folding to the inside for pleating (see below). You can trim with pinking shears, run a small machine stitch, sew a narrow hem, zigzag, or serge the edge.

Fold the skirt top to the inside a few inches allowing for the skirt length needed as mentioned above. Fold at least 1 inch to the inside and even more for additional support. Keep this turn under within 5 inches or so. This amount will taper around the top of your skirt in accordance to your marked lengths.

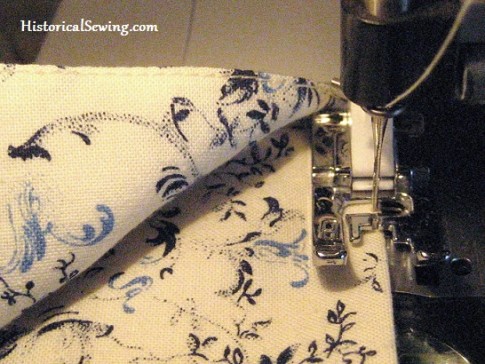

A machine edgestitch on the fold of the fabric is a modern tip that provides support and makes the whole pleating process easier.

Step 2: Mark

The first row of stitching works best at 1/8” to 1/4” down from the top fold. Additional rows should be between 1/4” and 3/4” down from the previous row, depending on fabric weight. The stitches themselves vary from 3/8” to 3/4” apart. Use these 5 tips, including how to mark your pleats, to keep them from looking like gathers.

Using a ruler, mark the entire length of fabric to be pleated with dots spaced according to your project. Mark all rows of stitching. Note: This will take some time – be patient!

A nifty sewing tool is Tiger Tape sold with quilting notions. The narrow tape is marked in 1/8″ lines. Place the tape along the skirt edge to make your dot marks. Remember to keep all dots in line with each other – along the horizontal rows as well as vertically (most important).

Step 3: Sew Pleating Threads

Cut a very long piece of thread. This should be nearly the length of the flat skirt width but could be shorter if you remember to pull up the pleats as you sew.

Use strong thread such as button thread or millinery thread. These pleating threads will remain in the fabric holding the pleats in place. If the thread breaks – the pleats come out.

Thread a long needle, such as an embroidery or millinery needle, and make a firm knot, leaving several inches of a tail.

Begin on the correct side of the skirt at the opening and make your stitches at each dot. Weave in and out of the fabric. Do not tie off the thread when you reach the end of your markings.

Repeat for additional rows. You can sew up to 5 rows depending on the fabric, but most 19th Century skirts have two to three rows. Some people find running all the rows at the same time faster than sewing each row separately.

Step 4: Finish Waistband and Pull Up Threads to Fit

Finish your waistband separately before attaching the pleats. The recommended width of your finished waistband should be 1” to 2”. You can also use a length of twill tape for the waistband.

Quarter mark your waistband and skirt. This will help space the pleats evenly.

When all the rows are sewn, grab all the thread ends and pull up together. Align right sides together of the skirt to the waistband. You do not need to pin every pleat but only every few to keep the pleats in place. Spend some time working out the pleat spacing. I like to pin every one to two inches.

Step 5: Sew To Waistband

Start attaching pleats to the waistband or tape using an overhand whipstitch. Sew two stitches into every pleat for a secure hold.

Finish by re-threading a needle onto the long tails left at the starting point and push them through to the wrong side. Tie the threads together.

After sewing, fold the waistband up, kicking the bottom fold of each pleat out. The top of the pleats will sit flat against the body.

If your pleats are very wide on the inside, you can fold them to one side (check from the garment’s right side to see which way you want them to lie) and tack down on top of each other on the inside. This will make them look more like flat knife pleats.

And if you are overthinking how to do all these pleats, take a look at my article here to ease your head.

I now have a full online class about creating cartridge pleats in a 19th century skirt project.

Have you cartridge pleated before? What do you think about the technique? Feel free to share any other tips you might have from your own sewing experience.

Hi Jennifer,

I was just wondering about attaching the pleated skirt to the waistband. Ordinarily the skirt top would be enclosed within the waistband. In this instance would I be correct in thinking that you finish off the waistband first and then sew the pleated skirt directly onto the bands lower finished edge without any further finishing? I was just a bit confused by your instructions when you got to that bit above.

Kind Regards

Faith

Yes, the waistband is completely finished separately (like a belt) then the top of the pleats are stitched to the bottom finished edge of it. The simple nature of cartridge pleats demand they are attached at the top and not enclosed as with other skirt waistbands.

Thank you so much for this tutorial!!

Although I have made several hisotrical costumes, I had never made cartridge pleats before and had been intimidated by how difficult I had presumed they were, but your tutorial helped me through it all and I am very pleased with my new 1670s skirt!

Yay! So glad you found it helpful.

Thanks for the clear instructions. I’m getting ready to sew a master’s robe and the pattern just calls for simple gathering, but I’m going to try cartridge pleating the sleeve fullness into the yoke. Someday I’d love to make my husband’s doctoral robe and if I can’t cartridge pleat properly there’s absolutely no hope of that.

Thank you for this wonderful tutorial. It was very helpful and gave me just what I needed to add the skirt to my French Fashion doll. The pictures of how to attach the skirt to the waist band were perfect!

I have gauged A few skirts. It is actually very fun and relaxing. And it’s amazing how you can get so much fabric on the waistband.

I went to several sites tonight looking for good information on cartridge pleating and yours was the best one I found. It made sense and the photos were terrific – I did use cartridge pleating once on a ante-bellum costume for my daughter but the pattern didn’t call them that and I used a machine to attach and really she was pleased enough but it didn’t look as good as it could have.

I have done a couple of garments with cartridge pleats, and am glad to know that I can possibly achieve a proper look with my Pullen pleater as I have tendinitis issues in my hand that can make handstitching a wee bit tedious.

I have used this on all my 1860s skirts since 1995.

It makes such a nice little ‘swinging hinged gate” over hoops. No twisting or pulling.

I’ve found that a quilt-weight cotton dress with three 45″ panels in the skirt almost always gathers to fit small to medium waists using my Pullen Pleater (We add panels and half-panels for larger waists). Sometimes, though, the threads break at the needles; then I have to improvise. I had troubles when using a heavier cotton–I was squeezing those pleats REALLY close together.

Thanks so much for this tutorial. These were just the pictures I needed to be sure how the pleats were attached to the waistband! I haven’t found any other sources that picture this so clearly!

Terrific tutorial! Cartridge pleats were also seen in 17th century America.

Thank you very much. It´s a great tutorial for someone like me who don´t know sewing. Thanks a lot.

I wish I had known this technique when I made an Irish Kinsale cloak. *sigh*

Thanks for the refresher. I tackled cartridge pleats for the first time back in 2008 . I was insane because I did them for a portfolio and audition. They turned out pretty well. The head of the department was impressed that I did them pretty well. Sometimes you have dive in for that great reward from learning. 🙂 I will be doing a lot of this this summer again.

Wonderful article! At last in process pictures. I was never sure how to hang the pleats from the waistband…inside, outside, both sides. Thank you.

This is just the tutorial I’ve been looking for – excellent instructions and detailed photographs. I’ll be making my first gauged dress in a few days and this is invaluable. Thank you!!

Love, love, love cartridge pleats…great tutorial!

Very nice! I just learned that in the 1860s, gauging stitches were usually alternate length (big on top, small underneath), so that the line of thread was close to the front of the pleats. Just another trick for keeping the pleats looking nice and even on the outside.

How timely! 🙂 I’m starting on my second try at a gauged skirt today! The part about how to sew them to the waistband was particularly helpful, since last time I sewed them to a hidden waistband where it didn’t matter if the stitches showed or not. I think I have discovered a new favorite way of taking up large skirts! 😀 Cartridge pleating looks so classy and finished.

Fantastic!!!! Cartridge pleating is one of my favorite historical sewing techniques. This tutorial is wonderful!

I have a trick to help with the spacing of the pleats. Sew a piece of light colored checked gingham to the turned down edge of the skirt. It adds stability to the pleats, especially on lightweight skirts, and insures accurate spacing of the pleats.

I too have used gingham to mark spacing for cartridge pleats and it made it so easy!

I was wanting to put cartridge pleats but need more fabric to do a proper turn down. Can I add fabric, perhaps the gingham to the top and fold it on the seamline? Or will that make it too hard to pleat?

Nope, sounds like a good idea to me if you run out of fabric. You will need to be careful of the seam allowance layers as you say. Depends on your fabric for how large to make it. 1/4″ is good or really wide, like 1″ so the pleats will sit even and not have a ridge where the allowance edges are on the inside.