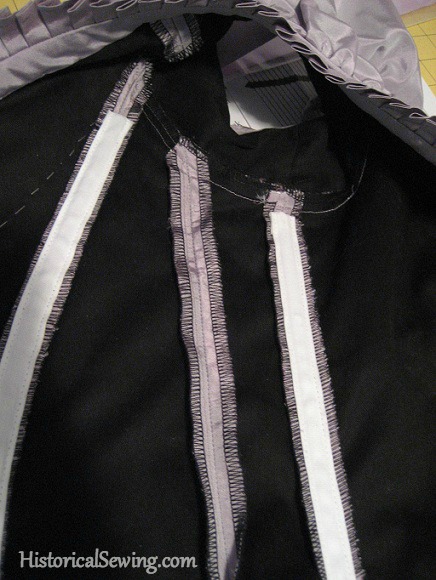

If you’re like me, as you sew up a garment you wonder how you’ll finish the raw edges of the seams. You know I cheat on nearly all my historical projects by serging the exposed raw edges.

But what if you don’t have a serger? Or don’t want to use something so modern as a zig-zag stitch with your machine? What other options are there to handle the raw edges left during or after sewing?

Let’s take a look at what you can use in your historical (and modern, for that matter) projects.

In my research of 19th century clothing I’ve found seven main ways they finished their seams… from super nice to raw & raveling. These methods are described below for your reference. Select the style you prefer based on your skill and the final finished look to your garment.

Hand Whipstitch

“THE” most used seam finish used in the Victorian Era. In my research over the years from examining my own personal collection of antique garments to photos of museum pieces, I’ve come across raw edges being hand whipped to finish more than any other method to treat them.

And why not? It’s super easy, handy, and can be done at many stages of construction.

To do this yourself, keep the stitches no more than 1/8” apart and about 1/8 to 1/4″ down into the seam allowance. Vary these recommendations according to your fabric – if it frays a lot or is tightly woven. Some fabrics will need more stitches and others less.

One strand of thread is fine. No need to use two unless you have fabric that frays or is bulky (jean or denim). Even then, varying your stitch width and depth will be more beneficial than a double strand of thread.

Don’t grade the seam allowance first. This will kind of defeat the full purpose of the whipstitching.

Both sides of the seam can be whipped together and the seam allowances pressed to one side or the seam pressed open and each half of the seam whipped separately.

On curved bodice seams, cut notches first and press open flat. Then do your hand whipstitch around the edges (or leave raw or bind, see below).

Bias Bound

A “fancy” seam finish still used in couture and high-quality fashion today is to bind the raw edges with bias tape – known today as the Hong Kong Finish.

Notch curved seams first, and press seams open before binding.

Use thin silk like China or habotai or even a thin taffeta to make your own bias strips to bind.

A modern substitute is packaged hem tape. Although, it’s generally polyester, so if that makes a difference to you keep that in mind before using or make your own. Packaged, narrow double fold bias tape is ok too but can be rather thick for binding seam allowances.

Sew the first side of the bias, right sides together, to the seam allowance. Sew this by machine or hand. Wrap the bias over the raw edge, tuck under the bias raw edge and hand whip or slipstitch to the back side of the seam allowance. You could also machine this second side.

Or bind in one step by hand sewing through all layers at once in a running stitch.

Leave Raw

Believe it or not, you’ll find a number of original garments with all the raw edges left as-is on the inside. Just sitting there looking like they don’t care. Or, at least, the dressmaker didn’t give a thought to neatening the edges. It wasn’t for competition anyways….

Although a HUGE time saver, leaving the seam edges raw is period correct but not necessarily the best method.

Through wearing (and cleaning), those edges are bound to fray even a little. If your seam allowance is less than 1/2″ then you risk the fabric shredding and, literally, coming apart at the seam.

I advise doing *something* with those edges, even if it is merely pinking them.

Pinking

Speaking of pinking…. The first patent for “pinking scissors” was in 1893. However, it wasn’t until 1931 when they were invented and patented (1934) into what we know them to be today.

I’ve seen Victorian garments with pinked edges, but it seems most were finished that way in the 20th century – perhaps for the dress-up box or theater use. Or perhaps we are lucky to find couture pieces that were hand pinked during construction like the Worth bodice shown above.

Pinking is a great way to keep your seam allowances flat – e.g. not making a bulky appearance on the correct side of the garment. It’s also easy and quick. Whoot! Well…. As long as your shears are sharp 😉

Flat Felled

This type of seam finish was mainly reserved for undergarments as it makes a sturdy seam. The seam is sewn then pressed to one side. The layer closest to the garment is trimmed short; the top layer edge is turned under and topstitched to the garment fully enclosing the raw seam allowance edges.

One thing to note here is that the topstitching is visible on the right side of the garment…. not really the best construction on a skirt or bodice. However, petticoats, chemise and drawers, bustles and hoops benefit greatly from this finishing method.

French Seam

I’m including this here as an alternative method, although not used often in the 19th century. French seams were mainly used only on sheer fabrics and undergarments. (The seam is constructed in two steps to fully enclose the raw edges.) I can’t recall seeing a true French seam on antique garments that are flatlined or cut from anything heavier than a sheer material. (Of course, you can always find exceptions.)

Seams were left exposed for a variety of reasons:

-It makes later alterations easier.

-The method of flatlining and not putting in a full lining in most things (a modern/20th century dressmaking technique) would create too much bulk for French seaming.

-The progress of dressmaking did not include French seams until later on. Those making clothes simply didn’t have it in their repertoire as something to use when creating garments.

Fold Under and Stitch (aka Hem)

A more 20th century devised method of dealing with raw edges….. Press the seam open. Then press under the seam allowance edge (towards the garment). Stitch this small hem of the seam allowance in place by machine.

It’s kind of like doing a one-turn hem on your seam allowances. Protects the actual raw edge from wearing out by not rubbing against the body/undergarments while giving a neat appearance when viewing the inside of the garment.

The c.1896 bodice shown above had the raw seam allowances of both fashion fabric and underlining turned into each other and topstitched by machine – a variation of the simple “fold under and stitch” but one that completely encloses the raw edges.

Modern Technique:

Serger/Overlock or Zig-Zag

Of course it’s not period correct, but it *is* my favorite method. I like to do it in the flatlining stage of both skirts and bodices instead of basting and then finishing the raw edges. 😉

As you construct your garment, think about the finishing of raw edges – mainly those on the seams; hems and necklines are generally finished other ways with facings or bias tape. Many times you’ll need to finish raw edges before continuing with other sewing steps.

What’s your favorite way to finish seam allowances?

How are these edges raw? I see whip stitching along all the edges. That usually is enough to prevent fraying.

As I can see, those seams are hand pinked as was common in 19th century bodices, and also whipstitched on most of them.

I am working on a 1880s-1890s project and I want to know if I can still use mantua-maker seams ?

I would be an older technique but still viable. I’ve not seen it used much at all that late in the century as sewing technology and methods of construction had changed. If you are wanting to go more historically accurate I would recommend flat fell or French seams instead.

When you hand whipstitch the seam allowances are you sewing them to the flatlining too or just binding them?

To finish the seam allowances, the hand stitches are more like binding the edge (which includes the fashion fabric and underlining too). If the seam allowances are tacked down to the bodice on the inside, then yes, the stitches only grab the underlining fabric.

Hei.

Was it just two layers used sew together as one piece of fabric?, no lining that cover-up all the seams and boning?, etc

MANY Victorian bodices were made with exposed seams. This was the long-running, contemporary dressmaking technique. Although, occasionally we will see extant bodices with a full lining attached to cover the inside seams, boning, closures, etc. But it wasn’t common yet. You can see examples and read more of both in my Linings & Underlinings post here.

This is a great source of knowledge. Kiss the hand, Madam.

I am writing a 1881-2 City Slicker Western, and the main character is a woman with a small anger management problem. She only murders seven in her three books. Half the murders she does are ‘good’ murders, one was on a bad hair day. Three were revenge murders. When she gets well off, murder is a waste of good revenge. She has a heart of silver. It don’t beat. Her friends though are golden. The first murder was so ice cold, she ended up with a never ending story, instead of being only a minor character in the first book, a simple Ambush at Salt Flats type, “A Mournful Wind.” The last of Elena/Mercedes’s books is ‘Tears on the Mountain’, the first two will get named eventually. It is a four book saga. Planned was only one.

I am closing in on the end. In the woman, Elena AKA Mercedes must be well dressed, in her profession she is leaving behind her, I’ve done as much research as possible on the net. As a man, have vast fields of ignorance, that I must gloss over. The nitty gritty of seams will be of great help in a scene I wrote, that I now see is lacking in content.

I expect to spend a couple of days, comparing what I have to what I might need. I did spend a lot of time on this. I do have the Spring Fashion of 1882 down well, in that information popped up on the net in exactly the right time.

When I started, it was hard to find information on corsets, much less anything else, and each year was more to find, until that was done. The other dress descriptions, were also gleaned from the net. This will be icing on the cake.

The Victorian Age is Ice Cold. A woman could never make a mistake, such as get raped or seduced…being alone with a man for five minutes could ruin her reputation; which was all she had. At 50 cents a day wages, a woman lived at home, with parents or husband, or starvation could force wrong decisions. I had no idea how horrible the Victorian Age was for women with out a good means of support.

Women Telegraphers were paid 1/3 less (the highest paid job an honest woman could have) and got stuck in whistle stops far from a saloon. Being alone were considered sensual. Woman’s liberation really started in 1880-81 as women became telephone operators with a living wage. Men had been late to work, rude and worst of all gossiped the business they over heard in saloons (for drink or money). Women were on time, cheerful and wouldn’t be caught dead in a saloon. I do have a couple of the early ones in my book. One from Leadville and the other was in Denver. It would take a few years for women who would work for less than a man and be happy in this case, to take over important part of the telephone industry.

I do bring in the great influence of Princess Alexandria, of England on Style; she is the Princess of the Princess style. Chokers or high collars were worn because she had a small scar on her neck. When she had rheumatic fever, and limped, there after, all of Society limped after her. She liked bangs, so all women in the ‘western’ world did too. One had a rat of old hair to make bangs (or other hair pieces) or bought them. The poor just cut bangs, not being able to change daily.

I have a 1914 Singer sewing machine. Any woman who could operate that did not lack anything in mechanical fitness.

Seamstresses were paid 50 cents a 12 hour day and had to take work home to finish. The more I read over that profession, the more impressed I am. The amount of fabric available that the woman who could afford a dressmaker knew is to me astounding.

Stuff was woolens….

A hand sewn Worth dress made on a manikin in Paris cost $350. One could get a dressmaker copy of the same dress (before the pattern hit the market) in Denver hand sewn for the same price. The more machine sewn the cheaper. Worth cuff’s are just as grand now as then…if someone wanted to upgrade a long armed dress, Worth is better than Coco Chanel.

I’m very happy to find this site. I will enjoy my self.

It’s me again. 🙂

I’m struggling with seam finishes for my 1890s gored skirt. I’ve worked on it, hoping for a moment of decisive insight, and none has come. The skirt is silk dupion with a cotton lawn underlining. It would take me days, literally, to whipstitch all the open seams, and I cry inside at the thought!

I don’t have an overlocker, and wouldn’t want to use one anyway, partly for reasons of historical accuracy and partly because I just do not like the finish and never have. As mentioned before, I like doing flat fell seams but they would leave a line of visible stitching on the outside of the skirt; and I like French seams but it is now too late for that. 🙂 I’m concerned that bias binding all the raw edges will result in a very bulky finish.

Were skirt seams usually finished that way in the late nineteeth century? Did dressmakers have teams of people who would sit for hours hand-overcasting long long seams on skirts…? What can I do that will finish off the seam, be historically correct and not cost me days?

Thanks everyone!

Sounds like, honestly, where you are to hand whipstitch them. Yes, it does take time. You can even pink them too and that would be faster. I wouldn’t do French seams on 1890s skirts because of the bulk. I suppose you could cut strips of bias wider than the pressed open seam allowances, press under the long raw edges and basically cover the entire seam allowance with this strip of bias. You’d need to hand tack it to the cotton underlining.

Thanks for those tips! I had a line of straight stitching in each seam allowance already, from where I attached the fashion fabric to the underlining, and what I’ve decided to do is pink the seam allowances down to that line of stitching. It’s quite solid, and I hope it will hold well. I know this finish in sometimes used in bodices, so I tell myself it isn’t too far off being period-correct. 🙂 My sewing deadline is now too close for me to be willing to spend a vast amount of time hand-finishing the long skirt seams.

In fact, I think I might be whipstitching and tacking in an unnecessarily time-consuming way. As for the whipstitching: when first I tried this stitch, on an armhole seam, I found that simply going into the fabric, up, over and back in, like a coil, produced a line of stitching that didn’t seem to do much in terms of stopping the fraying. My sewing club tutor – who is a very good modern seamstress who runs a successful bridal and formal-wear business but does not do historical sewing – recommended doing blanket stitch instead. I did this and found it much more successful, but it is also appreciably more time-consuming, at least for me! What would you recommend?

As far as tacking to an underlining is concerned, I find that the time-consuming thing is fishing for only one or two threads of the underlining fabric. It’s fine work and it can be rather fiddly. Is it possible to take up more than a few threads, so that the stitch inside the underlining is much the same size as the stitch inside the bias strip/facing/hem? Or would that not handle well or be secure?

I haven’t the time for any courses before my historical event, but once it is over I think I’ll take your Victorian undergarments online class. I’m starting to feel that I’m not managing to make progress anymore with my historical sewing because I haven’t got any tuition.

Thanks so much for all the useful information here!

Anna

A blanket stitch is like a whipstitch but adds the thread over the raw edges. In my research only a plain whipstitch was used in the 19th century. The key to holding those fraying edges is to make your stitches closer together and a bit deeper into the seam allowance.

Don’t pink too far into the seam allowance as it will weaken the seam and may cause the stitches to pull out/away from the fabric which opens the seam.

The thread or two take up you’re talking about is more a slipstitch. Making a more even running stitch between the seam allowance and underlining is just fine for what you’re doing.

Brilliant. Thanks for the advice about pinking. My pinking line is about half an inch from the seam, but if it goes wrong this time, I’ll simply know better next time!

I too hadn’t seen any indication of blanket stitching in photographs of nineteenth-century garments. I’ll try your whipstitching technique and see how it works.

I’m glad I can use a more even running stitch between the seam allowance and underlining. I don’t understand yet when this sort of running stitch is appropriate, and when I would need to use a slipstitch instead. Maybe a book on hand sewing could enlighten me.

You use whatever kind of stitch you need for how tight or sturdy you need to hold things together. Have you read my tutorial on the slipstitch?

I have an unrelated question but I have been meaning to ask you for a while. I am in the process of making my first victorian bustle dress and am looking for a quality silk at an affordable price but I don’t where to go! The only fabric stores near me are 45 minutes to an hour away and don’t seem to have what I am looking for. Silk online is ridiculously expensive and I feel like giving up which makes me really sad because I don’t want to crush my dreams. Anyway, I was wondering if you had any advice or websites that have the affordable silk I am looking for. Thank you so much! I love, love, love your work!

Thanks for reading and following Elle!

As for “quality silk at an affordable price” – well, you’re going to spend a good $10/yard and more for quality. For cheaper quality and not really accurate, you could go with a heavy slubby dupioni which you can probably find around $6/yd online. Silk taffeta – some of the best you can work with for bustle dresses – generally runs $18 to $24/yd but you might find some at $15/yd. Have you tried some of the fabric sale groups on Facebook? And for others, take a look at my vendor page here.

Don’t give up! Save up first and keep looking. Good luck!

I do mostly medieval sewing. I know back then they used weak glue to keep fabric from fraying, so something like Fraycheck (our modern equivalent) would be a permissible adaptation. I’ve also turned both edges in and used a running stitch to enclose the seam–sort of like flat felting without having the seam show on the front side. It holds up to laundering and over time.

Hi! A few things: Although pinking shears as we know them were invented late, it does not follow that all the pinking we see is a 20th C invention. I’ve rarely seen a late Victorian bodice without it. Instead, from the initial patent in 1892, it states this:

“My scissors or shears differ in principle from ordinary pinking irons or tools in the novel mode of operation just stated, as well as in their construction, and they are free from the objections of slowness of operation, and the performance of inaccurate Work as experienced with ordinary tools; with which tools, unless much time and care are expended, perfect work can be seldom produced; and my scissors or shears differ from pinking cutters which require the operator to place the tool at right angles to the edge of the fabric and keep it stationary while performing the pinking or `scalloping operation, from the fact that under my construction the scissors 0r shears require to be forced continuously through the fabric in the direction of the length of the blades, which is not practicable with pivoted pinking blades as heretofore constructed and operated. ”

There are two tools he mentions that are very interesting for conducting the job of pinking fabric – one is the pinking irons which can be seen on this page.

The other tool mentioned, the pinking cutter, is also shown on the above page. It’s a rotary blade cutter rather than shears. The rotary blade cutters were much earlier than the pinking shears. I’ve seen some unverified reports that some sort of pinking cutter was being used as early as the 1830’s. This makes logical sense given the amount of frilly trims of the 1830’s on the hems of skirts.

Also, seams aren’t always exposed. In fact, you start to see exposed seams right around the time the sewing machine becomes a household item. Before that, it’s rarer. To explain: This Example

The dress above is from the 1830’s. The picture of the inside of the bodice shows no exposed seams whatsoever. It’s all about keeping the seams hidden, mostly to protect them from wear (which is most likely, in the late 1890’s/early 1900’s, we see a lot of seams with bias trim over them).

In the 1850’s: Example

You see seams but the edges are typically like this – folded down and under. They still aren’t really exposed. This does help with alteration later on.

It’s the age of the sewing machine were you really see the exposed seams and the boning of the bodices starts to come into play: Example

It’s probably because it’s harder to do certain things on a sewing machine than by hand. For me, there are some garments where I always have to do hand finishes to make it look correct for the era – not just the “no machine stitches visible” but there are some bends, corners, or cuffs that simply won’t look right without hand sewing it. However, with the late Victorian, everything can be done on the machine without any issues.

Forgot to add the patents for a pinking machine! Seen Here

<- granted in 1882 but filed earlier and mentions "flared knives" as something that already exists

And here. < granted in 1890; it mentions pinking cutters being used as part of a way to cover dress stays.

Thanks for all your examples!

Thank you so much for the insightful post and comment. I really learned a lot! Before kids I did try most of these techniques on my costumes, but these days it’s almost always the serger.

Isabella, that was a fantastically informative post!

Could you possibly elaborate on the seam finishings used in the bodice of the 1830s dress that you posted? I’m trying to make a Regency dress for a charity ball and I’m finding it very hard to locate precise information about finishings used on curved seams during the Regency period. My dress is ivory silk jacquard. Even if I could do a flat-felled seam on the strongly curved back pieces of the bodice, I don’t think I would want to, as flat-felling produces a line of top-stitching visible next to the seam on the right side of the garment. I really don’t think that’s period-correct!

Any tips?

Jennifer, would you whipstitch?

Thanks! Anna

You could sew up the fashion fabric and lining separately THEN flatline and finish neck and hem. This c.1810 dress shows hand whipstitch around the armholes and the lining edges turned under and slipstitched together. This c.1815 spencer shows the back seams hand whipped. And this c.1795 bodice is showing the usual mantua maker seams (like flat fell) used at the time. Late 1830s dress bodice with hand whipped seams. And a early 1830s bodice with the back seams made with the faux curved seam by folding the fabric layers together and topstitching. Visible topstitching on the seams IS very period correct. Research a bit of late 18th century bodices and you’ll see where the construction method is coming from. Hope these links help!

The links certainly were helpful! Thank you – informative and so prompt as ever! I don’t know how you do it!

And I stand corrected. I should have phrased myself better; I IMAGINED that visible topstitching wouldn’t be thought attractive on delicate fabrics for ballgowns, but I honestly hadn’t investigated properly. Thanks for making me better informed!

That does make things easier. I have found that flat fell and French seams can actually be taken round significant curves provided they are clipped narrow enough. Not sure how much of a dressmaking aberration that is considered – my sewing tutor protests! – but it does seem to have worked for me so far!

One thing I didn’t quite understand: did you mean that I should flatline my bodice fabric AND make a lining, to attach at neckline and hem? If I can do topstitching, I was leaning towards simply flatlining the dress bodice in ivory cotton lawn, piece by piece, and then finishing the seams with narrow Frenchies/flat fells.

Either way, I’m sure I’ll enjoy my homework assignment to research late-18th century bodices. 🙂

Thanks!

Oh, your way sounds just fine! I meant to make up the fashion fabric (without flatlining first) and a full lining then mount them together. So basically flatline the full lining to the full bodice rather than in the separate bodice pieces.

Good luck!

Does the bodice lining stay in place nicely that way? Would you stitch it to the bodice at the waistline?

Thanks!

It should as the bodice panels are quite small. Baste to the neckline, armholes and waistline/bottom edge then finish those edges as usual (sleeves or bias, etc.).

Gotya! Thank you very much. You’re a legend.

PS I have my eye on your corded petticoat workbook. Once I’m done with my Regency ballgown and my 1893 ballgown, I have a dream of something 1840s. 🙂